By Angelo Boccato, freelance reporter

What role did the media play in the rise of the far right in Europe? Some, and at times many media, especially in the mainstream, have been central in normalising and sanitising the far-right, thus, consciously or unconsciously, providing them with a platform that makes them more presentable, and therefore electable.

Let’s look at Portugal.

On April 25 Portugal celebrates the Revolução dos Cravos (The Carnation Revolution) of 1974. This coup overthrew the dictatorial fascist Estado Novo (New State) regime which had been in charge since 1933 (led by Antonio Salazar between 1933 and 1968) and which, just like Francisco Franco’s regime in Spain, survived the falls of Mussolini and Hitler.

Coincidentally, April 25 is also a day of antifascist celebration in Italy, as since 1945 the country has celebrated the Liberation from Nazifascism and the valour of the Italian Resistance.

In both countries, however, the rise of the post-fascist far-right has made it even more complex to live a shared memory of democratic values.

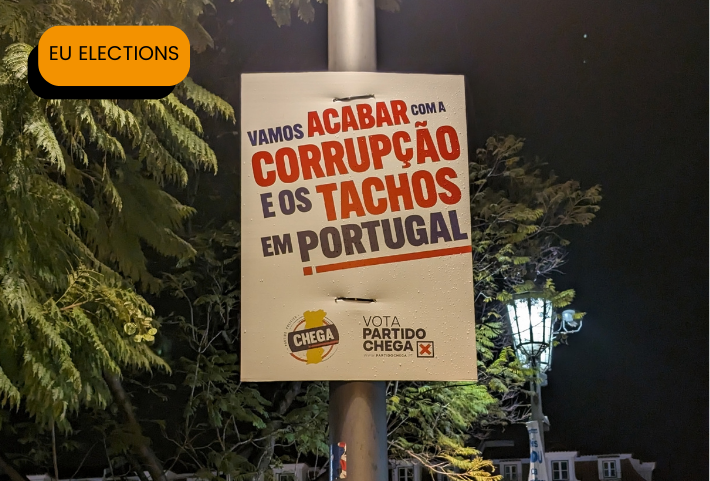

The Rise of Chega and its leader Andrè Ventura

Portugal was likely the last country in Western Europe, alongside Ireland, that had yet to experience the rise of a prominent far-right party in its political arena. The rise of Chega, (“Enough” in Portuguese) led by Andrè Ventura, has changed that state of affairs.

What was the role of Portuguese media in this instance?

“I don’t agree when they say that Chega’s success is due to the attention it receives from us, journalists. It’s curious because admitting this is the same as admitting that we, journalists, have enormous power – while the activists themselves and the party severely criticise the press, to say the least. It is worth mentioning that parties like Chega are very active on social media. They work with influencers, and a whole powerful network. It’s an unfair battle because journalism requires context, it’s complex and very different while digital media production doesn’t play according to the same rules,” Amanda Lima, a Brazilian journalist based in Portugal, reporter at Diáro de Noticias, and analyst for CNN Portugal tells MDI.

In addition to this, how did Chega became so relevant in the Portuguese political arena in just a few years?

“Chega’s rise was very predictable, given the movements that we journalists have observed in recent months, such as the protest vote, discontent with the policies of the former government, and, of course, a portion of voters who identify with the racist and xenophobic stance that the party presents on many occasions. The skillful way they use social media is also an important factor. Ventura, alone, has more followers than the other candidates combined,.” adds Lima.

“I think the reason Portugal resisted this radical populist movement for longer is due to the country’s history, and the strength of democracy here, but it was obvious that it would happen sooner or later. The far-right movements work very well together globally and their campaigns are very efficient.”

Another parallel between post-fascist parties is the celebration of mottos around religion, nationalism, and family, Lima observes. “It is not news that several Chega activists and some deputies are nostalgic for Salazar’s dictatorial regime. The very slogan they have used “God, Country and Family” is a reference to the dictator. More recently, this supportive stance became clearer in two symbolic moments. One was the time they sang “Gândola, Vila Morena”, in a parliamentary session commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 25th of April. The deputies saw the moment as something “leftist” or “communist”, not as a celebration of democracy.”

“It shows that they don’t see Salazar as a dictator, which is what he was. And that’s not an opinion, it’s just a proven fact.”

Chega has gone from a 7.2% electoral result and twelve seats in 2019, to 18.1% of the votes, with fifty seats assigned in the 230 seats of the Assembly of the Republic in 2024. Tthe two main parties, the centre-right Alianca Democratica (Democratic Alliance) and the Partido Socialista (Socialist Party) won respectively 28.8% and 28% of the votes, with eighty seats for the former and seventy-eight for the latter.

This situation left Chega in a position of great influence, as Luís Montenegro’s Alianca Democratica ended up forming a minority government. The rise of the party and the impact of its leader is not unlike the one of Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

A country with robust press freedom

“In addition to the reasons I have already mentioned, Chega’s success is due to André Ventura, who is a very skilled politician. This type of populist movement only works if it has a leader, like Trump, Bolsonaro, and more recently Javier Milei from Argentina. Ventura uses many of the tactics of other leaders of the global far right.

“During the campaign, he pointed out the use of fake news and the collaboration between Chega and the Bolsonaro family: Eduardo Bolsonaro, one of Bolsonaro’s sons, was in Portugal at the beginning of the year and held meetings and debates with Chega members, including Ventura himself. They act as a network and make it very clear in their social media posts. Even the style of the publications is similar,” said Lima.

Covering the far-right, from established parties to the fringe neo-Nazi and neo-fascists is not an easy choice, and can expose them to a lot of dangers.

Lima, for instance, has suffered a lot of intimidation and threats, in her case both of xenophobic and sexist nature.

“They try to disqualify us at any cost. It is much worse for women journalists. They attack our integrity. Male colleagues do not suffer sexual attacks, for example, and this says a lot about the contempt they feel for women. In Portugal, I have the additional challenge of being an immigrant and that is the first thing that is used against me as if I cannot do my job here, even though I can and am duly qualified to do it. “Go back to your homeland” is one of the phrases you hear most often,” comments Lima.

According to Reporters sans Frontieres (Reporters without Borders) 2024 Index, Portugal ranks seventh (among 180 countries analysed) in terms of press freedom, however, the report points out that while press freedom in the country is “robust…[journalists] face legal, economic and security challenges”.

Portugal is an important example of how the far-right’s rise can also occur in countries with robust press freedom and where similar forces did not previously occupy a space in the political arena. It’s a call for constant vigilance.

Chega’s result in the upcoming European elections will be an important test for the development and expansion of the far-right on the continent.

Picture from Shutterstock

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Media Diversity Institute. Any question or comment should be addressed to editor@media-diversity.org