By Faris Zebib, YocoJoin correspondent

The echo of chants filled the Place du Luxembourg, just outside the European Parliament. The Eurocrat hotspot in the centre of Brussels, Belgium, was now the scene of a battle for the rights of people more than 3,000 kilometres away. There the war raged on; here they stood united, demanding justice.

Just before my university lecture in Ixelles, I decided to stop by and join in. The square was full of young people of a similar age. As someone of Palestinian descent, it felt strange – and encouraging – to see people with no direct connection to the Middle East, not by name, culture, ethnicity or proximity, taking part in such a protest.

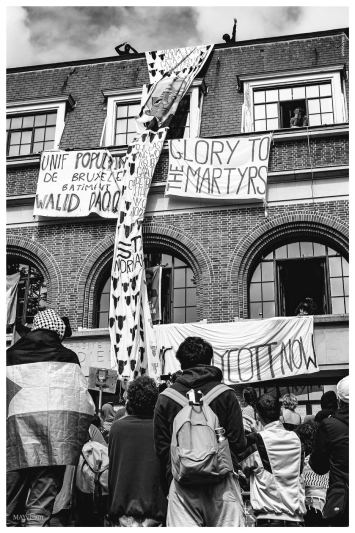

A protest in front of the European Parliament, 2024.

Since the start of the war in Gaza in 2023, universities around the world have been the scene of protests and occupations by students, academics and staff. The Israeli army’s invasion of the Palestinian territory in response to the 7 October attack by Hamas has been heavily criticised on campuses, with many pointing to the disproportionate amount of violence and destruction unleashed during the conflict. While the fragile ceasefire agreed between Israel and Hamas in January 2025 brought hope to some, Donald Trump’s recent announcement that the United States would take control of Gaza and expel its inhabitants reminds us that the fate of the Palestinians and their territories still hangs in the balance.

In recent months, the stirrings of the conflict have been felt in Belgium, where universities have been the scene of heated debates on what stance to take. Should European universities cut ties with their Israeli counterparts? For some students, the answer is a resounding “yes”.

The spring of 2024 saw a flurry of occupations on many Belgian campuses. The first university occupation in Belgium began at the University of Ghent (UGhent) – one of the country’s most prestigious universities, and its second largest campus – on 6 May. The organisations Ghent Students for Palestine and End Fossil Ghent occupied the premises, demanding that the institution cut ties with Israel and present a more transparent climate action policy. The movement drew about 100 students.

Just one day later, a similar occupation took place at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). In less than ten days, students organised similar movements in various universities, including the Vrije Universiteit van Brussel (ULB’s Dutch-speaking counterpart), KU Leuven, the Université de Liège (ULiège) and the Université Catholique de Louvain (UCL). The demands were similar: Belgian universities should cease all cooperation with Israeli counterparts, from student exchanges, research projects, etc.

For the students involved, the occupations have also been an opportunity to express outrage at the Belgian government’s approach to the ongoing war and to reclaim a narrative they feel has been largely neglected in the mainstream media. But for some, the reason for getting involved is simpler than that: to show compassion and solidarity with the people of Gaza. “You are a human being, and you have a minimum [level] of empathy”, explains Martin (the name has been changed), a student who took part in the occupation at the ULB. “On a psychological level, there is no need for more than that to be involved and motivated by the cause. There is no need for more than that. There is no need [for the protests] to be politicised.”

The Toll of War

More than a year after the 7 October attacks by Hamas, Gaza lies in ruins. According to the Gazan Ministry of Health, the current estimated death toll is over 46,000, although the destruction of hospitals, schools, and infrastructure has made it extremely difficult to track casualties accurately. A recent academic paper published in The Lancet suggests that the real figure could be as high as 186,000 or more.

The Gaza Strip is home to over 2 million Palestinians, most of whom are refugees or descendants of refugees displaced since the 1948 “Nakba” when half of the indigenous Palestinian population was violently expelled from their homes and territories.

Since 2007, Gaza has been under the political rule of Hamas and a stringent blockade by Israel out of fear of dual-use goods. This has severely restricted Gaza’s access to basic goods and freedom of movement, further exacerbating the humanitarian crisis, and was considered unlawful under international law by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in 2011.

Since last year, numerous international organizations like Amnesty International and UN experts have declared grounds for an ongoing genocide in Gaza. This, combined with the ICC issuing arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Minister of Defence, Yoav Gallant, gives the international community ample grounds to act. The ceasefire between Israel and Hamas remained but a distant hope at the time of the occupations in the spring of 2024. Faced with an ongoing tragedy and what they saw as a lack of response from the Belgian government, students took it upon themselves to call for an academic boycott of Israeli institutions, hoping for their voices to be heard.

The occupations weren’t just a rejection of relations with Israel, but an opposition to the ties that bind Belgian universities to institutions that have contributed, whether actively or indirectly, to the war effort.

Israeli Institutions Under Scrutiny

The links between Israeli academic institutions and the ‘apartheid’ system used to systematically oppress Palestinians and actively break international law are well documented. In her book ‘Towers of Ivory and Steel: How Israeli Universities Deny Palestinian Freedom (Verso Books, 2024), Maya Wind, an Israeli academic and expert on militarism, policing, and security, examines the role played by these institutions. She highlights the active partnerships between university institutions and military forces. These include the innovation of repressive and destructive technologies, the active marginalisation of Palestinian voices, and the perpetuation of structural inequalities.

The ongoing war has seen a number of such collaborations flourish. Tel Aviv University (TAU), the largest campus in Israel, announced the creation of a ‘war room’ in October 2024, allowing its engineering department to collaborate with the military. In a video shared on X, the institution highlights two examples of technologies that emerged from this ‘war room’: the first is a camera system used to attach to canine units, which have been documented with mauling civilians across Gaza. The second is mobile phone chargers compatible with Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) tanks. Other cooperation programmes exist within the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the University of Haifa and the Israel Institute of Technology (Technion). “Universities, many teaching human rights, international law, and preaching for equality, have shown a hypocritical stance,” says one student from the occupations.

In an open letter published in the Belgian newspaper Le Soir in November 2024, a collective of academics called for a boycott of Israeli universities and companies, demanding that they be excluded from European funding programmes. Israel is regularly involved – through programs such as Horizon Europe – in EU-funded scientific projects. Some of these projects have raised concerns in the past, mainly due to the possible development of dual-use technologies. Through Horizon 2020 – which ran from 2014 to 2020 – Israeli institutions received €1.27 billion in funding.

“With so many critical Israelis collectively calling for a boycott, the traditional rhetoric that an academic and economic boycott would also affect Israelis critical of their government, and that such a boycott would stifle the few remaining dissenting voices, can – at last – be consigned to oblivion,” the second collective said in its open letter. “The opposite seems to be happening: it is precisely because of the lack of international pressure that the massacres continue, and that Israeli society and the few critical voices are increasingly losing their grip on government policy.”

Resistance and results: the academic boycott’s impact

Overall, did the boycotts make a difference? On both an individual and institutional level, yes. Venues cancelled, job opportunities refused, academic articles rejected … Since the beginning of the war, Israeli academics have faced unprecedented opposition from their European counterparts.

As far as the occupations in Belgium are concerned, results have been mixed. While some universities, such as UGhent and ULB, severed most, if not all, ties with Israeli institutions after the protests, not all demonstrations achieved the same goal. A report by independent academics at KU Leuven, uncovered over 30 different research projects with Israeli universities. Despite the large-scale protests since the start of the war, the KUL ethics committee reviewed the existing collaborations and chose not to terminate them. “We did not manage to get what we wanted”, said students involved in the occupation. “[The KUL rectorate] threatened us with legal action, with a court order forcing us to leave [on the 6 September].”

This follows legal proceedings against students involved in the occupation. Despite the university’s decisions and actions, the protestors have continued their activism, even blocking access to the rectorate in November 2024.

On 10 July, after two months of occupation, the VUB decided to respond. They vowed to set up a human rights committee to evaluate future collaborations, provide a fund for Palestinian students, and plant an olive tree recognising martyrs in Gaza. However, the continued insistence on maintaining research projects left students frustrated. When they voiced their concerns, the rectorate simply replied: “Unless you stop now, I’m going to remove all the good things that you’ve succeeded in getting, including the Palestinian students fund”. Students have continued their activism, launching another occupation in October 2024.

While UCL initially claimed to have no partnerships with Israeli universities, students uncovered a joint project called MultiSpin.AI involving both the Belgian institution and the Bar-Ilan University in Israel, which has ties with the Israeli arms manufacturer Elbit Systems and whose faculty of engineering has hosted, on at least one occasion, a hackathon in partnership with the IDF. UCL agreed to suspend student exchanges but stopped short of cutting all ties. “The most they offered us was to put the Palestinian flag up, it was a real slap in the face to us”, said one student.

At the end of January 2025, the Flemish Interuniversity Council announced that it would no longer enter into new cooperation agreements with Israeli partners involved in serious human rights violations.

Regardless of the varying success of the occupations, the student movements have broken down cultural, linguistic, and physical barriers across Belgium. “We weren’t sure if we were going to occupy the university, but when we saw the ULB start its occupation on 7 May, we decided to follow”, one VUB student recalls.

This mobilisation brought students with little previous experience and knowledge into a new community, as one activist explains: “I didn’t know anyone who was going to do it, but I realised that being shy is not what matters right now. So I pushed myself out of my comfort zone and went”.

When asked about the ULB occupation’s cooperation with the neighbouring VUB, one activist declared: “We are more than a coalition, we are family, friends, comrades.”

In every single occupation, every single protest, every single movement, you will find people coming from all over Belgium to support each other: “If one of us couldn’t speak Dutch or French, we would communicate in English. There were always people happy to translate, and we made an effort to improve our languages together.”

Writing this article, I couldn’t help but feel hopeful. To see bridges being built across the country, on behalf of people thousands of miles away.

Will Europe listen?

As the EU navigates its role in the war in Gaza, students remind us that moral leadership often begins not in parliaments, but on campuses.

Belgian students refuse to remain complicit in the oppression of Palestinians. Their activism has already shaped policy and forced institutions to rethink long-standing collaborations. Students across the country have fought for morality, stood in solidarity and made their stance on what is right and wrong very clear. Everyone always has a choice. Will you join their call for humanity?

Disclaimer:

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the Media Diversity Institute Global. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Media Diversity Institute. Any question or comment should be addressed to [email protected]